https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLwr8DnSlIMg0KABru36pg4CvbfkhBofAi

Visual Studio 2019 Community Edition, CUDA 11.0.

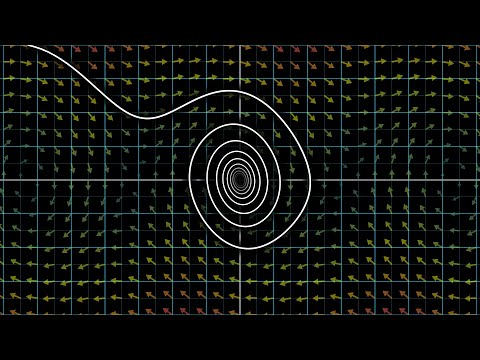

This is a hobby project. Before I started it, I was curious about how to simulate the airfoil lift in a simple and principally correct way. After digging up several sources I decided to test an elegant and simple concept of Newtonian lift. Although this is an oversimplified concept of how wings work, the core idea seems to be fundamentally correct.

As for now the physical model is based on the DEM (Discrete element method) description of the ideal gas, but it can be easily extended up to SPH (Smoothed-particle hydrodynamics) if simulating real gases or complex phenomena are required. It's also possible to suit the application to simulate fluids by replacing the core equation with a corresponding one, e.g. Navier-Stokes.

The mathematical model of the simulation is the ideal gas model. It has the following properties and capabilities:

- The gas is monatomic.

- The collisions between atoms and airfoil are partially inelastic.

- The collision response is based on Hooke's law, i.e. via the spring-damper equation.

- The model is capable of simulating wave propagation.

- The model is capable of simulating turbulence.

The benefit of this approach is that it was easy to develop, debug and test. And it could provide me a solid ground for further improvements to mesh-free SPH method. The individual properties of particles are:

- Velocity

- Position

- Pressure (for visualization purposes only)

- Mass and radius are common properties.

The simulator consists of two independent parts:

- The state renderer

- The simulation module itself

These modules are designed to be weakly coupled and do not depend on each other. It's technically possible to perform a simulation offline and render it later. As for now, the rendering occurs after several simulation steps.

The phase space is a widely used concept in all sorts of simulations. The main idea is the simulation variables are represented as a multidimensional vector. This vector denotes a point in the "phase space". The simulation process is actually just a movement through this space.

This representation is convenient because we can express the movement of this point as an Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) dx/dt = f(x, t), where x is the sim state and f is a black-box function that gets current state and calculates derivative, i.e. direction and rate of change of state variables. Whatever f is, the simulation process is just a simple integration of this ODE.

For detailed information please see 'Differential Equation Basics' and 'Particle Dynamics' topics of this course: https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~baraff/sigcourse/

Additional source is 3Blue1Brown Youtube channel:

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLZHQObOWTQDNPOjrT6KVlfJuKtYTftqH6

This simulation uses the Forward Euler method with an adaptive time step. Although the course mentioned above offers an algorithm based on error assessment (see 'Differential Equation Basics' lecture notes, section 3, 'Adaptive Stepsizes'), this simulation uses the largest free path to determine the time step.

I have tried several options such as the 4th order Runge-Kutta and error-based adaptive step size, but I ended up with the Forward Euler method as the most practical solution in this particular real-time demo. In this case, RK4 gives unnecessary precision with a higher computational cost, which is overkill. But I might return to it, or even add a sophisticated symplectic integrator when I switch to SPH.

The main algorithm of the derivative solver is the following:

void CDerivativeSolver::Derive(const OdeState_t& curState, OdeState_t& outDerivative)

{

BuildParticlesTree(curState);

ReorderParticles(curState);

ResolveParticleParticleCollisions();

ResolveParticleWingCollisions();

ParticleToWall();

ApplyGravity();

BuildDerivative(curState, outDerivative);

}To find collisions between particles or particles and the wing the BVH-tree is used. The particles tree is constructed at every step.

To speed up construction I used Tero Karras' approach:

The tree is based on the Z-order curve. The curve is also extremely useful to reorder particles after tree construction to restore coalesced memory access. After reordering I got 35% overall speedup, from 8 FPS to 12 FPS on 2'097'152 on 1080 Ti. The Z-order curve increases the probability of getting nearby particles in the same memory transaction. I've borrowed this idea from SpaceX presentation (the link with the time code):

https://youtu.be/vYA0f6R5KAI?t=1689

This was the first version of the simulation. As a first step, I made a single-threaded three construction and traversal. My Core i7 7700k could simulate 16'384 particles at about 15 FPS. This simulation took about 15 minutes of real-time:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PiH9ogvN6RY&list=PLwr8DnSlIMg0KABru36pg4CvbfkhBofAi&index=4

The further step I made was to parallelize as much as I could. I ended up with almost the same amount of simulation time (about 10 minutes, 18 FPS), but now the number of particles was increased up to 131'072 on 4 core (8 threads) CPU:

To parallelize I used C++ 17 std::execution::par_unseq feature, which gave me 94% CPU utilization.

The CPU version gave me a playground to overcome math problems. I switched to GPU when the math model had been done.

The first naive CUDA implementation had the same performance as the CPU one. But I managed to increase the number of particles up to 2'097'152 at the same computational cost when I'd done the recommended optimizations. The optimizations were the following:

- Minimizing Divergence section

- Reordering particles along Z-order curve

- Using shared memory as stack storage instead of a local array.

- Doing collision responses immediately during tree-traversal. This has increased thread divergence but reduced memory workload significantly.

I'd like to go further and switch to the SPH method to improve simulation quality. This can be simply done via changing equations in ResolveParticleParticleCollisionsKernel and expanding the bounding box of a single particle to cover the smoothing area instead of just its circle area.

I was experimenting with OpenCL API via Boost.Compute. I had an idea to run the simulation on an integrated GPU into my Intel CPU. The idea was to use CPU, Intel GPU, and Nvidia GPU together by sharing the same ODE state by building the particles tree partially on each device. Then just share these trees among them.

However, my investigation has shown that the data transfer between the devices degrades all benefits. So I've put the idea off.