Space is hard, especially if you haven’t done it before. A growing number of CubeSats are launched by small, inexperienced teams every year, and a number of them fail due to missing some small but critical hardware or software problem. Researchers from the Robotic Exploration Lab (REx) at Carnegie Melon University have learned some of these lessons the hard way and created PyCubed, an open-source hardware and software framework for future CubeSats.

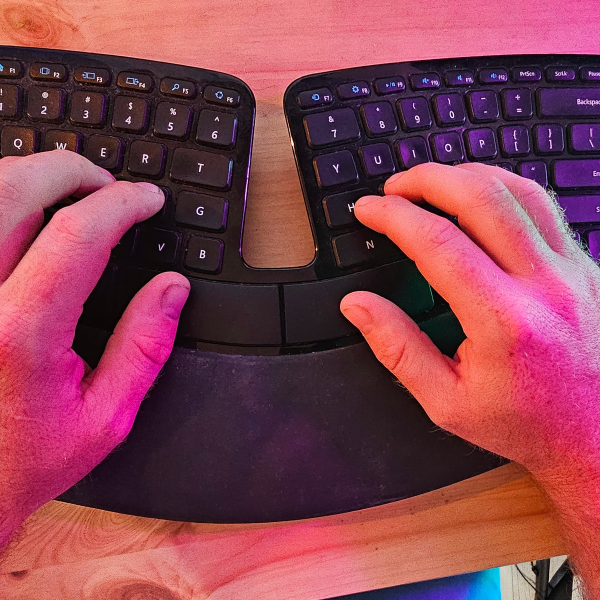

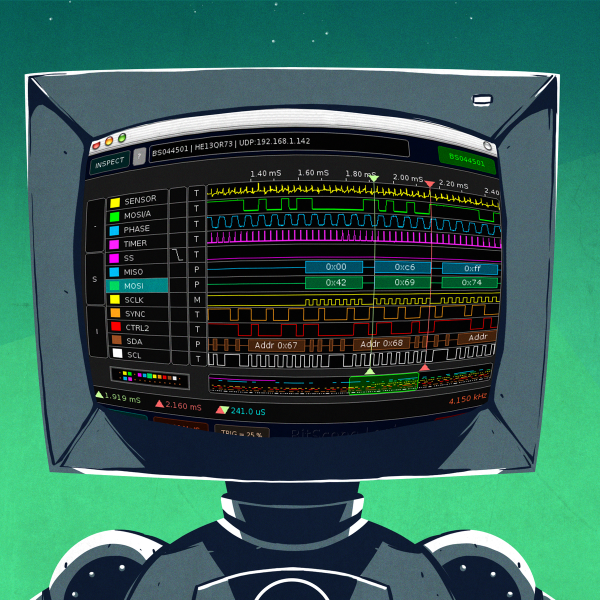

Most satellites, including CubeSats, require the same basic building blocks. These include ADCS (Attitude Determination and Control System), TT&C (telemetry, track, and command), C&DH (command and data handling), and an EPS (electrical power system). Each of these building blocks is integrated into a single PC/104 size PCB. The main microcontroller is an ATSAMD51, also used on a couple of Adafruit dev boards, and runs Circuit Python. Communications are handled by a LoRa radio module, and there is also an unpopulated footprint for a second radio. An LSM9DS1 IMU and an optional GPS handle navigation and attitude determination, and a flash chip and micro SD card provide RAM and data storage. The EPS consists of an energy harvester and battery charger, power monitor, and regular, that can connect to external Li-Ion batteries and solar panels. Two power relays and a series of MOSFETs connected to burn wires are used to deploy the CubeSat and its antennas.

On the PCB there are standardized footprints for up to four unique payloads for the specific missions. The hardware and software are documented on GitHub, including testing and a complete document on all the design decisions and their justifications. The PyCubed was also presented at the 2019 AIAA/USU Conference on Small Satellites. The platform has already been flight-tested as part of the Kicksat-2 mission, and will also be used in the upcoming V-R3X, Pandasat, and Pycubed-1 projects.

This is not the first open-source CubeSat we’ve seen, and we expect these platforms to become more common. Tracking a CubeSat is a lot less expensive than sending one to space, and can be done for as little as $25.

Just a question:

If I order in these boards and develop a Cubesat. Should I do a burn in and cherry pick the best boards?

Or throw caution to the wind? Send up two?

Can someone explain this to me? Can you actually build your own satellite? How do you get it to space? Who do you pay, how much does it cost?

The first garage built satellite went up in December 1961, Project OSCAR built it and then negotiated to get it into space as part of an existing launch.

That was the first non-government satellite in orbit (I think no commercial satellites were up by that point) and it proved there could be secondary payloads.

After that, it became easier to net a launch, but more competition. Ham satellites went up from time to time. But eventually it became a thing, lots of universities wanting a launch.

So now you see articles like this, yes anyone can build a satellite, but to get it into space you have to meet standards, and have to find a launch.

Those two things are way harder than building the satellite.

You can get books about building satellites, and cubesats have a standard size and form so that’s been worked out, I think you can buy off the shelf casing now. If you need send data to earth, Amsat will gladly supply communication boards, if the satellite can be used by hams after the experiment is over.

But there’s no guarantee of getting into space.

I remember attending to a nice talk about the open source UPSat at FOSDEM 2018. It was quite interesting.

You can see it there: https://archive.fosdem.org/2018/schedule/event/upsat/

Hi! Max here. I designed PyCubed and did the hardware/software/firmware for V-R3x as well. We’re running mission ops now, but so far the V-R3x mission has been a resounding success! Long story short, running these sats entirely on CircuitPython has been instrumental in allowing easy over-the-air tweaks. More to come.

V-R3x is using my latest PyCubed boards that I haven’t pushed to the public repo yet. There’s some novel protection circuit stuff that I need to publish on (PhD thesis and whatnot) before I should release- but its coming asap!

Great work Max! We (Libre Space Foundation) can help on the radio part of your design to make it more space comms friendly and compatible with our global ground station network SatNOGS. See here https://gitlab.com/librespacefoundation/pq9ish/pq9ish-comms-vu-hw/ and feel free to join our community https://app.element.io/?#/room/#librespace:matrix.org

Please dont use LoRa in space and especially in radio amateur frequencies. More details:

https://community.libre.space/t/lora-protocol-in-space/7275/3

The tape measure antennas are adorable![1]

1. Antennae vs. Antennas

https://grammarist.com/usage/antennae-antennas/

In the U.S. and Canada, the plural of the noun antenna is antennae when the word denotes the flexible sensory appendages on insects and other animals. But when the word refers to a metallic apparatus for sending or receiving electromagnetic signals, American and Canadian writers usually use antennas. British writers tend to use antennae for both purposes. Australian and New Zealand writers are split on the matter, using both plurals for the metallic devices.

Example

Publications throughout the English-speaking world use antennae as the plural of the animal appendage—for example:

Her gold face, with black-edged jaws, coral-like antennae and those deep black eyes, was cracked. [Guardian]

The scientist explains how lobsters use their antennae to communicate during mass migrations. [Wall Street Journal]

[I]ts antennae have an additional fixation point to help stabilize it during jumping. [Nigerian Daily Independent]

American, Canadian, and some Australian and New Zealand writers use antennas as the plural of the metallic receiver:

As well as installing and providing the set-top boxes, the government’s scheme will adjust antennas. [Sydney Morning Herald]

They also finished wiring up antennas, work left over from the first spacewalk. [USA Today]

The only noise that could be heard was that of Canucks flags secured to antennas and side windows flapping in the wind. [Vancouver Sun]

British writers often (not always) use antennae for both purposes—for example:

Each wire, in close proximity to passengers’ seats, acts as internal antennae allowing phones to operate at very low power levels. [Daily Mail]

Information gathered by the cars’ antennae could include parts of an email, text or photograph. [Telegraph]