Weird mystery of watery plumes on Europa may hint at 'stealth particles'

Deposits from Europa's plumes remain elusive.

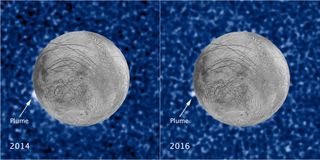

In 2012, the Hubble Space Telescope caught a glimpse of a faint plume of material at the southern pole of Jupiter's moon, Europa. Since then, the moon has provided faint glimmers of plumes, hinting that material from its icy interior ocean could be jetting into space.

Now, a new study thatcombed images of the moon to hunt for signs of material on the Europanlandscape, only to find no obvious indications of the eruptions.

In 1995, NASA's Galileo mission arrived at the Jupiter system and began a detailed probe of the gas giants and its moons, including Europa. Europa was also visited by NASA's Voyager and New Horizons spacecraft on their way out of the solar system. By using data collected by all three missions, Paul Schenk, a researcher at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, was able to hunt for signs of changes that could indicate erupting material had fallen back onto the surface. The plumes themselves could help to reveal information about the ocean hidden deep beneath the ice.

Related: The plumes of Europa are missing "hotspot" engines

"Plumes on icy bodies usually produce a range of particle sizes," Schenk told Space.com via email. Gravity pulls the largest and most massive of the particles back to the surface. "These particles are always different from the surface in some way, either by composition and color or by particle size and hence apparent brightness," he said. "So we expected to see some sort of anomalous brightness or color signature near the sources, wherever they may be."

But Schenk found no variations in brightness or composition that might indicate ocean material might have ended up on the surface of the moon.

The surprising lack of variations could mean that plume activity was relatively continuous over the three decades of mapping, the exuded particles blending together over time with no obvious differences. Another option is that the plumes produced "stealth" deposits not visible with the available instruments. Finally, the plumes themselves could be atypical, not really plumes at all but something unseen on other worlds.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We do not really know why we do not see an obvious sign of plumes on Europa's surface," Schenk said. "We will have to go there to find out."

"Stealth plumes" and hidden fingerprints

On the surface, Europa appears rather unremarkable, a grey and white world with traces of intriguing red patches. The entire moon is covered with ice, hiding an ocean beneath. The interaction of the ocean with rocky layers beneath could provide a haven for life to evolve, especially if the oceans contain vents that bring heat up from the interior.

Since 2012, Hubble has spotted several indications of explosive activity as the moon has passed between Earth and Jupiter. During some of the passages, light from Jupiter was blocked by vapor venting from the moon's surface.

Europa isn't the first moon known to have explosive plumes. Saturn's moon Enceladus is well known for spewing material from its 'tiger stripe' crevices at its southern pole. NASA's Cassini mission flew through one of the eruptions to obtain a sample of the material, which the spacecraft was not originally designed to collect and examine.

When NASA's Europa Clipper mission arrives at the moon in the 2030s, it will be better prepared for plumes. The spacecraft will carry the Mass Spectrometer for Planetary Exploration/Europa (MASPEX), which will collect gases around the moon and analyze any plume material that may be released into space. To do so, the spacecraft must fly by the regions where material is being expelled. Identifying those regions prior to the spacecraft arrival would make the process easier.

Using the maps created by the three missions, Schenk created new maps that revealed how the surface evolved over time. Changing features would appear as larger dark or bright features distinct from the static, unchanging landscape on the moon. But the new maps revealed no major changes larger than 30 miles (50 kilometers) on the surface.

Next, Schenk specifically probed the candidate plume sites, regions identified based on where plumes had been spotted over Europa. Image coverage for the south pole sites identified by Hubble was poor, and no obvious features were visible.

"Plumes may not produce observable deposits in existing imaging," Schenk wrote in his paper, which was published March 24 in the Astrophysical Journal Letters. "This is possible if Europa's plumes are vapor-only 'stealth plumes', but the failure of water vapor to crystalize into particulates upon venting into space would be difficult to explain."

The difference in size between vented particles and surface particles should be different enough to be spotted by the spacecraft, even if they lay thin on the ground. However, if stealth plumes are the norm, mid-infrared or ultraviolet mapping spectrometry may be required to detect them. Clipper will carry a digital camera sensitive to ultraviolet wavelengths and may be able to spot the traces.

The chaos of Europa

Puzzling regions known as chaos terrain could potentially produce short-term plumes and may hide their fingerprints. Hundreds of chaos regions are scattered across the moon's surface, with domes and iceburglike blocks. As the bottom layer of surface ice is heated by tidal interactions between Jupiter and Europa, the surface buckles in on itself and creating stress fractures. The ice on top weakens and the crust buckles and sinks, forming larger, glacierlike blocks of ice.

Schenk said that these violent events could expose liquid water on the surface for short periods of times. That water could boil off to produce localized plumes of frozen water vapor crystals. There are faint indications around the terrains that could be fingerprints of the plumes.

"We might be observing this at scales of a few kilometers in the form of dark halos around some chaos [terrain], but we are not sure," Schenk said.

Another possibility is that the extensive chasms stretching over 600 miles (1,000 kilometers) across the surface of Europa could be expelling material. Occasionally the chasms contain double ridges with dark reddish materials coating the surfaces up to 6 miles (10 km) along the sides. Previous research has suggested that the burnished red material along the flanks could come from explosive venting from the chasms, much as water vapor jets from the central fissures along the double ridges of Enceladus.

"If the darker reddish materials flanking double ridges on Europa are due to venting of plume materials like those on Enceladus, they would have been spectacular," Schenk said. During eruptions, the ridges would have released material along most of their length, creating long curtains of gas and particles several kilometers high arcing into space above each ridge, though it is unlikely they all exploded at once.

"It would have been quite a thrill to be standing there, in a spacesuit, watching these events along ridges that disappear over the horizon," Schenk said.

The new results underscore the limited quantity and low quality of images of the moon. Clipper plans to undertake an extensive hunt for plume activity, with hopefully more success. Until then, the plumes may remain a mystery, Schenk said.

"Whatever is going on at Europa, we haven't gotten to the bottom of it yet."

- NASA's Europa Clipper Mission to Jupiter's Icy Moon Clears Big Hurdle on Path to Launch

- Europa Report: Jupiter's Icy Moon Explained (Infographic)

- 6 Most Likely Places for Alien Life in the Solar System

Follow Nola on Facebook and on Twitter at @NolaTRedd. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

<a href="https://www.space.com/your-favorite-magazines-space-science-deal-discount.html" data-link-merchant="space.com"" target="_blank">OFFER: Save 45% on 'All About Space' 'How it Works' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of <a href="https://www.space.com/your-favorite-magazines-space-science-deal-discount.html" data-link-merchant="space.com"" data-link-merchant="space.com"" target="_blank">our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd